A new report has highlighted how three top prominent executives initially found themselves at odds in early deliberations about Apple's App Tracking Transparency framework.

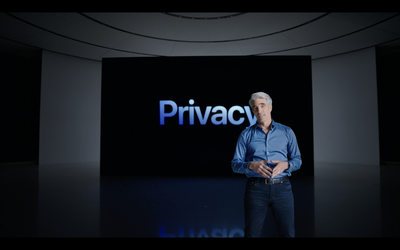

According to the report from The Information, the executives who disagreed over how far Apple should go in protecting user privacy in digital advertising included Apple's Craig Federighi, who oversees software engineering, Phil Schiller, who manages the App Store, and Eddy Cue, Apple's head of services.

In 2020, Apple rolled out App Tracking Transparency, a feature that lets users decide whether a specific app can track them across other apps and websites.

From a technical standpoint, ATT hides a user's identifier for advertisers, also known as IDFA, from apps that a user has not approved. Eric Neuenschwander, the birther of the identifier, began to raise concerns over IDFA and how it was being used by apps to unethically track users, according to the report.

Eventually, the ad industry began to use the IDFA in ways the privacy engineering team hadn't intended, building an entire tracking ecosystem around it. Unscrupulous developers started using it to gather location data on users and sell that information to data brokers for additional revenue.

Around this time, Neuenschwander privately began telling colleagues he regretted creating the IDFA, in part because others like Google followed with a similar identifier a year later, according to people who have worked with him.

Even before ATT, Apple gave users the ability to enable "Limit ad tracking" in iPhone settings. The toggle, however, was buried deep in the Settings app and often untouched by users.

Neuenschwander's team, around 2016, started to find new ways to enforce a user's choice if they enabled "Limit ad tracking," including out-right hiding the identifier from apps if a user had indicated they did not want to be tracked.

As those efforts did not curtail the improper use of IDFA, Apple's head of software engineering stepped in to move forward with what would later become known as ATT.

According to the report, the idea of ATT first came around in 2019, when Federighi told Eric Neuenschwander "to do something about IDFA." Federighi had agreed to allocate some resources of the software engineering department to those efforts, calling it a "tentpole" idea, implying it could be showcased on-stage during an event.

As those efforts were underway, Apple's executives found themselves in disagreement, according to sources cited in the report familiar with internal meetings at Apple.

Before Apple could make any such public announcement, three Apple senior vice presidents—Federighi, Cue and Schiller—had to come to a consensus about how far the feature would go in crimping tracking and how Apple could soften the expected impact the changes would have on developers.

Schiller, who runs the App Store, was concerned over how a framework like ATT could impact the App Store ecosystem and mobile ads that run within apps.

Schiller and his aides warned that "if new restrictions on the IDFA resulted in users seeing fewer ads, they might download fewer apps," leading to fewer app downloads and potentially fewer in-app purchases, which Apple takes a cut of.

Cue, who was in charge of Apple's iAd network, was concerned that ATT would go too far in eliminating tracking. "Cue's team was especially sensitive to the consequences of kneecapping the IDFA," the report notes.

Federighi, on the other hand, was all-for a framework such as ATT. Federighi "oversaw a team of privacy-minded engineers who wanted to curtail the powers of an Apple tool that unscrupulous advertising companies, mobile developers and data brokers were exploiting to track the behavior of iPhone users," The Information reports.

The varying opinions of Apple's top executives eventually led to the final version of ATT, which offers a simple prompt to users when they first open an app on whether they wanted to be tracked or not.

![]()

According to the report, Apple's initial idea for ATT was to let users disable tracking across all apps, but part of the concession reached by the executives was to offer a toggle for each app.

The trio eventually settled on a plan: iPhone users would have a choice of whether to opt into app tracking, which Apple executives felt was more defensible if developers and the online advertising industry pushed back, people familiar with the discussions said. They would also be able to do this on a per-app basis, which Apple executives also felt would benefit advertisers, a person familiar with the matter said. This was a big change from Apple's earlier IDFA controls, which enabled tracking across all apps by default.

In the fall of 2019, Federighi tasked members of his software engineering department to begin developing ATT and have it ready by June 2020, when Apple would officially showcase it on-stage during its Worldwide Developers Conference.

In the nine months leading up to the conference, members of Federighi's team consulted with Apple's lawyers to "tread carefully around decisions that could raise regulators' eyebrows." Federighi's team was rigorous in their planning of ATT, even debating whether "tracking" was the right choice of word and carefully designing the prompt users would see when they first open an app.

In response to the report, an Apple spokesperson told The Information that Apple's teams work collaboratively across the company "putting the same effort into privacy innovation as we put into all of our product designs, and the result is greater choice and superior products for our customers."

The Information's full report is an interesting read that details the industry response to ATT and the creation of IDFA.