Apple in early 2019 removed or restricted many popular screen time and parental control apps on the App Store due to their use of Mobile Device Management, or MDM, which the company said put user security and privacy at risk.

![]()

During today's antitrust hearing with the U.S. House Judiciary Antitrust Subcommittee, Cook was questioned about Apple's decision to remove the parental control apps, which came after the release of Apple's own Screen Time feature.

Cook said what Apple has said multiple times before, that the apps that used Mobile Device Management to allow parents to limit kids access to their devices placed data at risk. "We were worried about the safety of kids," Cook said.

Cook's statement was similar to what Apple said when the apps were removed: "These apps were using an enterprise technology that provided them access to kids' highly sensitive personal data. We do not think it is O.K. for any apps to help data companies track or optimize advertising of kids."

The Congresswoman questioning Cook asked about a specific app from the Saudi Arabian government that also used MDM, but Cook said he was not familiar with the app and that he would have to provide more data at a later date. When questioned about whether Apple applies different rules to different app developers, Cook once again said that rules are applied to all developers equally.

Cook was asked about the timing of the removal of the parental control apps, given that Screen Time had launched not too long before, a question that Cook largely skirted. He was asked why Phil Schiller had referred customers complaining about the removal of parental control apps to Screen Time, but Cook referenced the more than 30 parental control apps in the App Store and said there is "vibrant competition" in the parental control space in the App Store.

When pressed on whether Apple has the power to exclude apps from the App Store or remove competing apps, Cook returned to what he said during his opening statement, that there's a "wide gate" for the App Store, referring to the fact that there are more than 1.7 million apps available. "It's an economic miracle," said Cook. "We want to get every app we can on the App Store."

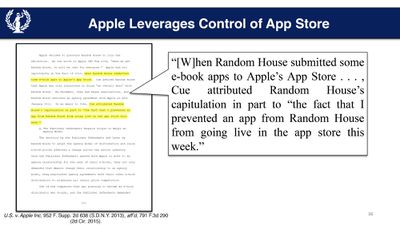

In tandem with the questioning on parental control apps, Cook was asked why, in 2010, Apple used the App Store to push publisher Random House into participating in the iBookstore, which Random House had declined to do. In a cited document, Apple iTunes chief Eddy Cue at the time emailed Steve Jobs that he "prevented an app from Random House from going live in the App Store," because Apple was aiming to get Random House to agree to an overall deal. Cook in response said there are "many reasons" an app might not make it through the approval process. "It might not work properly," he said.

Apple's 2019 decision to limit parental control apps led the developers of those apps to call for a public API that would allow them to access the same features that are available in Screen Time after the MDM options were restricted, which Apple declined to provide.

Mobile Device Management, which the apps used, is a feature that is specifically designed for enterprise users to manage company-owned devices. Apple's position is that the use of MDM by consumer-focused apps has privacy and security concerns that have been referenced in App Store guidelines since 2017.

Rather than providing an API, Apple ultimately decided to allow parental control app developers to use Mobile Device Management for their apps, with stricter privacy controls that prevent them from selling, using, or disclosing data to third parties. Apps must also submit an MDM capability request that evaluates how an app will use MDM to prevent abuse and to ensure no data is shared. MDM requests are re-evaluated each year.