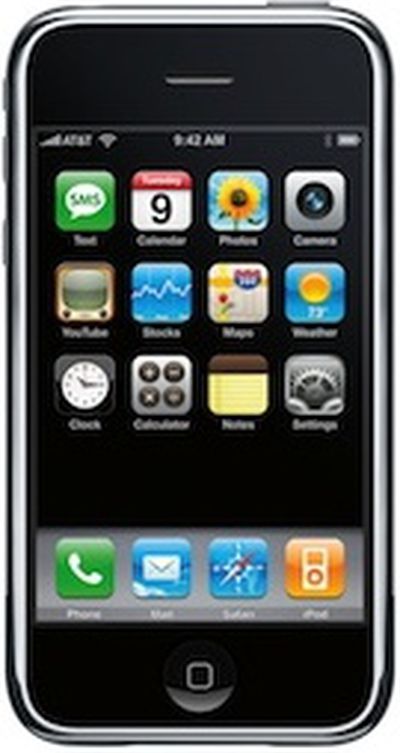

Just ahead of the second anniversary of Steve Jobs’ death, Fred Vogelstein has published a piece in The New York Times that gives a detailed behind-the-scenes look at the work that went into both the first iPhone and its January 9, 2007 announcement, featuring information from key iPhone developers like Andy Grignon, Tony Fadell, and Scott Forstall.

Just ahead of the second anniversary of Steve Jobs’ death, Fred Vogelstein has published a piece in The New York Times that gives a detailed behind-the-scenes look at the work that went into both the first iPhone and its January 9, 2007 announcement, featuring information from key iPhone developers like Andy Grignon, Tony Fadell, and Scott Forstall.

According to Andy Grignon, the senior manager in charge of the radios of the iPhone, the night before the iPhone announcement was terrifying. Jobs had insisted on a live presentation of the prototype iPhone, which was still in the developmental stages, often "randomly dropping calls, losing its Internet connection, freezing, or simply shutting down."

The iPhone could play a section of a song or a video, but it couldn’t play an entire clip reliably without crashing. It worked fine if you sent an e-mail and then surfed the Web. If you did those things in reverse, however, it might not. Hours of trial and error had helped the iPhone team develop what engineers called “the golden path,” a specific set of tasks, performed in a specific way and order, that made the phone look as if it worked.

At the time of the announcement, only 100 iPhones existed, with some of those featuring significant quality issues like scuff marks and gaps between the screen and the plastic edge. The software, too, was full of bugs, leading the team to set up multiple iPhones to overcome memory issues and restarts. Because of the phone’s penchant for crashing, it was programmed to display a full five-bar connection at all times.

Then, with Jobs’s approval, they preprogrammed the phone’s display to always show five bars of signal strength regardless of its true strength. The chances of the radio’s crashing during the few minutes that Jobs would use it to make a call were small, but the chances of its crashing at some point during the 90-minute presentation were high. "If the radio crashed and restarted, as we suspected it might, we didn’t want people in the audience to see that," Grignon says. "So we just hard-coded it to always show five bars."

Apple had poured all of its efforts into the iPhone, and its success largely hinged on a flawless presentation. As described by Grignon, there was no backup plan in place if the presentation was a failure, which put enormous pressure on the team.

Jobs rarely backed himself into corners like this. He was well known as a taskmaster, seeming to know just how hard he could push his staff so that it delivered the impossible. But he always had a backup, a Plan B, that he could go to if his timetable was off.

But the iPhone was the only cool new thing Apple was working on. The iPhone had been such an all-encompassing project at Apple that this time there was no backup plan.

Though there were a huge number of factors that could have caused the presentation to fail, it famously went off without a hitch. Grignon shares a final story on how the engineers and managers that worked on both the iPhone and the presentation shared a flask of Scotch as they watched "the best demo any of us had ever seen."

The full piece, which explores thoughts from other key Apple employees like Tony Fadell and Scott Forstall, is well worth a read. It covers the overwhelming complexity of developing an entirely new product and the extreme lengths that Jobs and his team went to keeping the product a secret.